Objects that use colormaps by default linearly map the colors in the colormap from data values vmin to vmax. For example:

pcm = ax.pcolormesh(x, y, Z, vmin=-1., vmax=1., cmap='RdBu_r')

will map the data in Z linearly from -1 to +1, so Z=0 will give a color at the center of the colormap RdBu_r (white in this case).

Matplotlib does this mapping in two steps, with a normalization from

[0,1] occurring first, and then mapping onto the indices in the

colormap. Normalizations are classes defined in the

matplotlib.colors() module. The default, linear normalization is

matplotlib.colors.Normalize().

Artists that map data to color pass the arguments vmin and vmax to

construct a matplotlib.colors.Normalize() instance, then call it:

In [1]: import matplotlib as mpl

In [2]: norm = mpl.colors.Normalize(vmin=-1.,vmax=1.)

In [3]: norm(0.)

Out[3]: 0.5

However, there are sometimes cases where it is useful to map data to colormaps in a non-linear fashion.

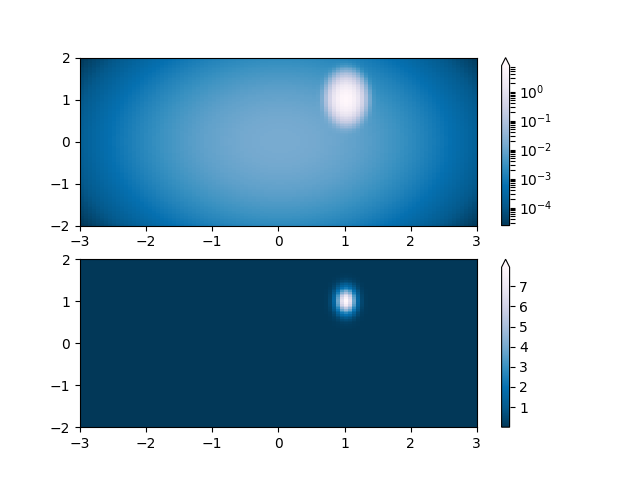

One of the most common transformations is to plot data by taking

its logarithm (to the base-10). This transformation is useful to

display changes across disparate scales. Using colors.LogNorm()

normalizes the data via  . In the example below,

there are two bumps, one much smaller than the other. Using

. In the example below,

there are two bumps, one much smaller than the other. Using

colors.LogNorm(), the shape and location of each bump can clearly

be seen:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.colors as colors

from matplotlib.mlab import bivariate_normal

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[-3:3:complex(0, N), -2:2:complex(0, N)]

# A low hump with a spike coming out of the top right. Needs to have

# z/colour axis on a log scale so we see both hump and spike. linear

# scale only shows the spike.

Z1 = bivariate_normal(X, Y, 0.1, 0.2, 1.0, 1.0) + \

0.1 * bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1)

pcm = ax[0].pcolor(X, Y, Z1,

norm=colors.LogNorm(vmin=Z1.min(), vmax=Z1.max()),

cmap='PuBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[0], extend='max')

pcm = ax[1].pcolor(X, Y, Z1, cmap='PuBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[1], extend='max')

fig.show()

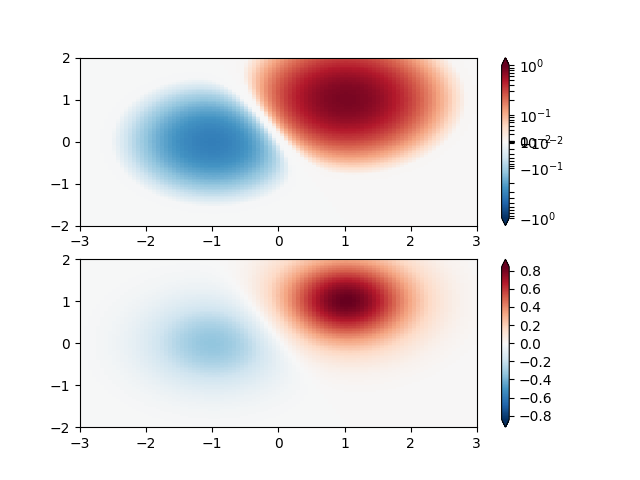

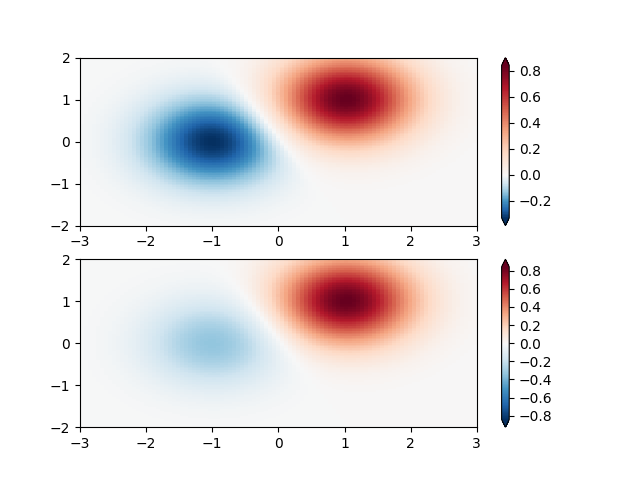

Similarly, it sometimes happens that there is data that is positive

and negative, but we would still like a logarithmic scaling applied to

both. In this case, the negative numbers are also scaled

logarithmically, and mapped to smaller numbers; e.g., if vmin=-vmax,

then they the negative numbers are mapped from 0 to 0.5 and the

positive from 0.5 to 1.

Since the logarithm of values close to zero tends toward infinity, a small range around zero needs to be mapped linearly. The parameter linthresh allows the user to specify the size of this range (-linthresh, linthresh). The size of this range in the colormap is set by linscale. When linscale == 1.0 (the default), the space used for the positive and negative halves of the linear range will be equal to one decade in the logarithmic range.

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[-3:3:complex(0, N), -2:2:complex(0, N)]

Z1 = (bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1., 1., 1.0, 1.0))**2 \

- 0.4 * (bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1.0, 1.0, -1.0, 0.0))**2

Z1 = Z1/0.03

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1)

pcm = ax[0].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1,

norm=colors.SymLogNorm(linthresh=0.03, linscale=0.03,

vmin=-1.0, vmax=1.0),

cmap='RdBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[0], extend='both')

pcm = ax[1].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1, cmap='RdBu_r', vmin=-np.max(Z1))

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[1], extend='both')

fig.show()

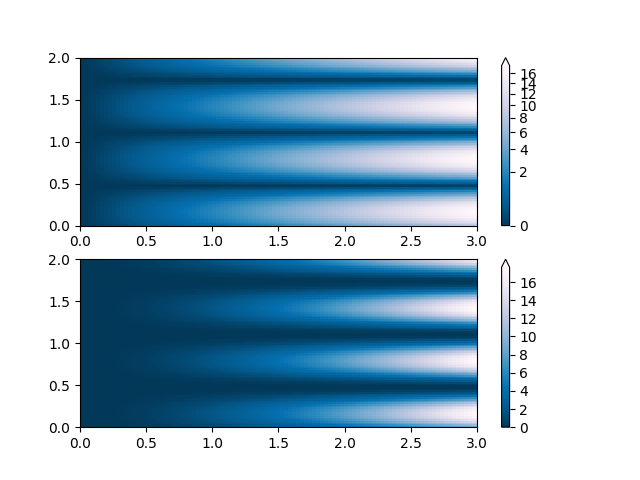

Sometimes it is useful to remap the colors onto a power-law

relationship (i.e.  , where

, where  is the

power). For this we use the

is the

power). For this we use the colors.PowerNorm(). It takes as an

argument gamma (gamma == 1.0 will just yield the default linear

normalization):

Note

There should probably be a good reason for plotting the data using this type of transformation. Technical viewers are used to linear and logarithmic axes and data transformations. Power laws are less common, and viewers should explicitly be made aware that they have been used.

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[0:3:complex(0, N), 0:2:complex(0, N)]

Z1 = (1 + np.sin(Y * 10.)) * X**(2.)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1)

pcm = ax[0].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1, norm=colors.PowerNorm(gamma=1./2.),

cmap='PuBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[0], extend='max')

pcm = ax[1].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1, cmap='PuBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[1], extend='max')

fig.show()

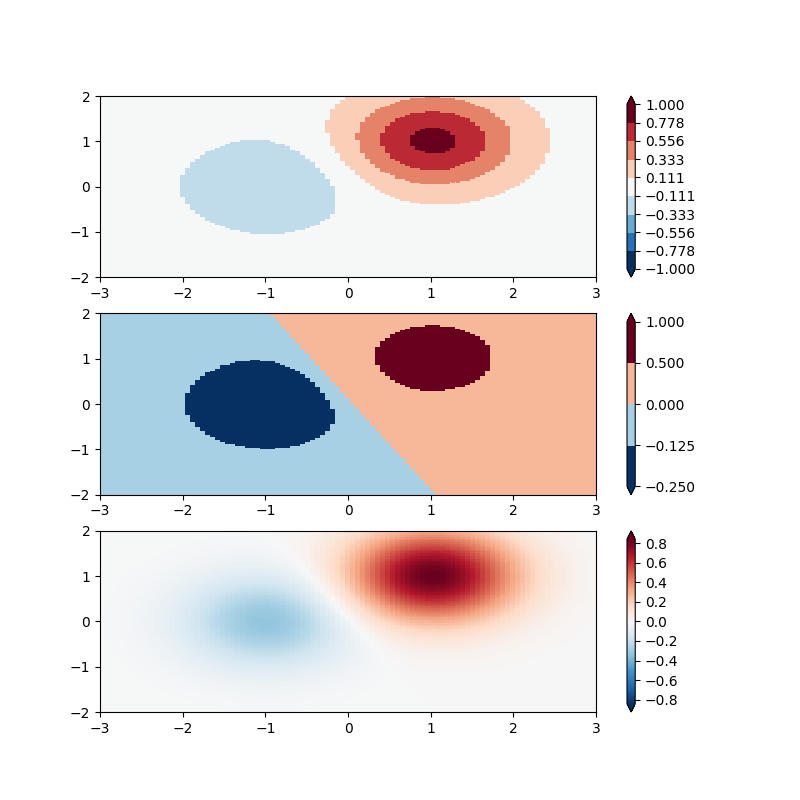

Another normaization that comes with matplolib is

colors.BoundaryNorm(). In addition to vmin and vmax, this

takes as arguments boundaries between which data is to be mapped. The

colors are then linearly distributed between these “bounds”. For

instance:

In [4]: import matplotlib.colors as colors

In [5]: bounds = np.array([-0.25, -0.125, 0, 0.5, 1])

In [6]: norm = colors.BoundaryNorm(boundaries=bounds, ncolors=4)

In [7]: print(norm([-0.2,-0.15,-0.02, 0.3, 0.8, 0.99]))

[0 0 1 2 3 3]

Note unlike the other norms, this norm returns values from 0 to ncolors-1.

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[-3:3:complex(0, N), -2:2:complex(0, N)]

Z1 = (bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1., 1., 1.0, 1.0))**2 \

- 0.4 * (bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1.0, 1.0, -1.0, 0.0))**2

Z1 = Z1/0.03

fig, ax = plt.subplots(3, 1, figsize=(8, 8))

ax = ax.flatten()

# even bounds gives a contour-like effect

bounds = np.linspace(-1, 1, 10)

norm = colors.BoundaryNorm(boundaries=bounds, ncolors=256)

pcm = ax[0].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1,

norm=norm,

cmap='RdBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[0], extend='both', orientation='vertical')

# uneven bounds changes the colormapping:

bounds = np.array([-0.25, -0.125, 0, 0.5, 1])

norm = colors.BoundaryNorm(boundaries=bounds, ncolors=256)

pcm = ax[1].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1, norm=norm, cmap='RdBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[1], extend='both', orientation='vertical')

pcm = ax[2].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1, cmap='RdBu_r', vmin=-np.max(Z1))

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[2], extend='both', orientation='vertical')

fig.show()

It is possible to define your own normalization. In the following

example, we modify colors:SymLogNorm() to use different linear

maps for the negative data values and the positive. (Note that this

example is simple, and does not validate inputs or account for complex

cases such as masked data)

Note

This may appear soon as colors.OffsetNorm().

As above, non-symmetric mapping of data to color is non-standard practice for quantitative data, and should only be used advisedly. A practical example is having an ocean/land colormap where the land and ocean data span different ranges.

N = 100

X, Y = np.mgrid[-3:3:complex(0, N), -2:2:complex(0, N)]

Z1 = (bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1., 1., 1.0, 1.0))**2 \

- 0.4 * (bivariate_normal(X, Y, 1.0, 1.0, -1.0, 0.0))**2

Z1 = Z1/0.03

class MidpointNormalize(colors.Normalize):

def __init__(self, vmin=None, vmax=None, midpoint=None, clip=False):

self.midpoint = midpoint

colors.Normalize.__init__(self, vmin, vmax, clip)

def __call__(self, value, clip=None):

# I'm ignoring masked values and all kinds of edge cases to make a

# simple example...

x, y = [self.vmin, self.midpoint, self.vmax], [0, 0.5, 1]

return np.ma.masked_array(np.interp(value, x, y))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1)

pcm = ax[0].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1,

norm=MidpointNormalize(midpoint=0.),

cmap='RdBu_r')

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[0], extend='both')

pcm = ax[1].pcolormesh(X, Y, Z1, cmap='RdBu_r', vmin=-np.max(Z1))

fig.colorbar(pcm, ax=ax[1], extend='both')

fig.show()

Total running time of the script: ( 0 minutes 3.692 seconds)