This tutorial aims to show the beginning, middle, and end of a single visualization using Matplotlib. We’ll begin with some raw data and end by saving a figure of a customized visualization. Along the way we’ll try to highlight some neat features and best-practices using Matplotlib.

Note

This tutorial is based off of this excellent blog post by Chris Moffitt. It was transformed into this tutorial by Chris Holdgraf.

Matplotlib has two interfaces. The first is an object-oriented (OO)

interface. In this case, we utilize an instance of axes.Axes

in order to render visualizations on an instance of figure.Figure.

The second is based on MATLAB and uses

a state-based interface. This is encapsulated in the pyplot

module. See the pyplot tutorials

for a more in-depth look at the pyplot interface.

Most of the terms are straightforward but the main thing to remember is that:

We call methods that do the plotting directly from the Axes, which gives us much more flexibility and power in customizing our plot. See the object-oriented examples for many examples of how this approach is used.

Note

In general, try to use the object-oriented interface over the pyplot interface.

We’ll use the data from the post from which this tutorial was derived. It contains sales information for a number of companies.

# sphinx_gallery_thumbnail_number = 10

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.ticker import FuncFormatter

data = {'Barton LLC': 109438.50,

'Frami, Hills and Schmidt': 103569.59,

'Fritsch, Russel and Anderson': 112214.71,

'Jerde-Hilpert': 112591.43,

'Keeling LLC': 100934.30,

'Koepp Ltd': 103660.54,

'Kulas Inc': 137351.96,

'Trantow-Barrows': 123381.38,

'White-Trantow': 135841.99,

'Will LLC': 104437.60}

group_data = list(data.values())

group_names = list(data.keys())

group_mean = np.mean(group_data)

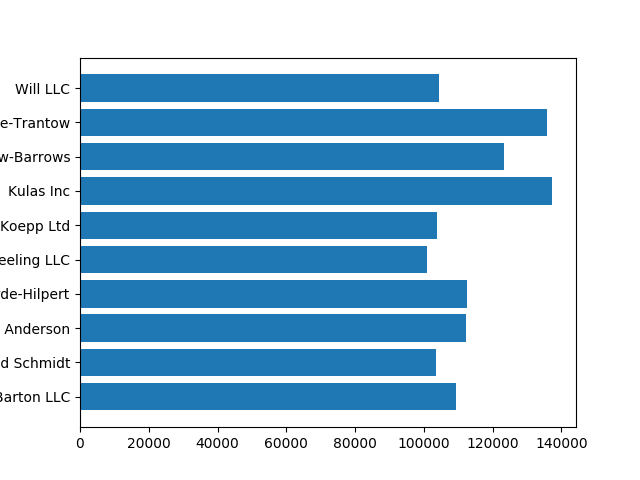

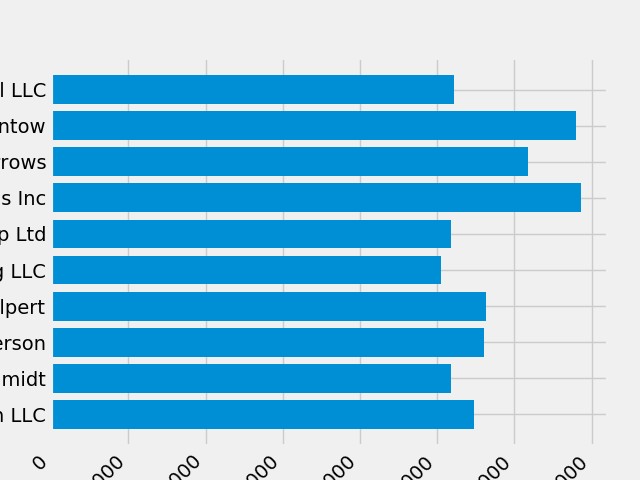

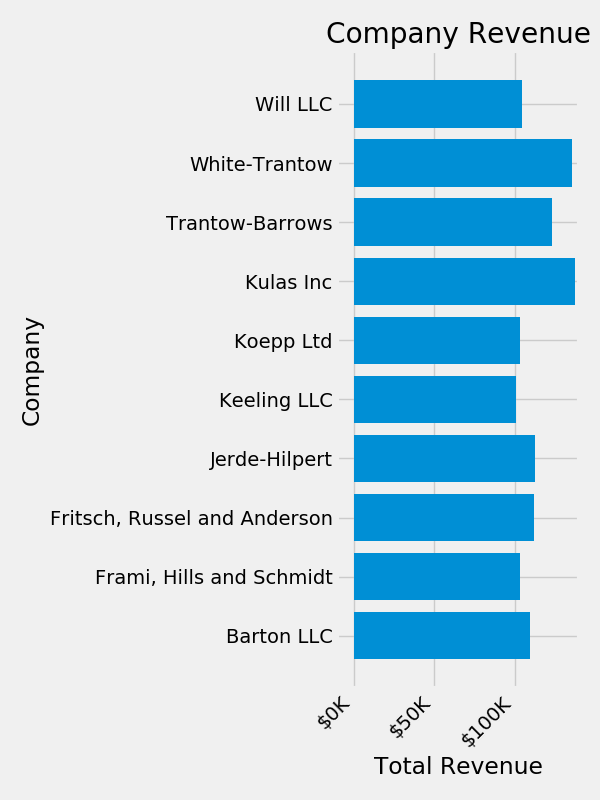

This data is naturally visualized as a barplot, with one bar per

group. To do this with the object-oriented approach, we’ll first generate

an instance of figure.Figure and

axes.Axes. The Figure is like a canvas, and the Axes

is a part of that canvas on which we will make a particular visualization.

Note

Figures can have multiple axes on them. For information on how to do this, see the Tight Layout tutorial.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

Now that we have an Axes instance, we can plot on top of it.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

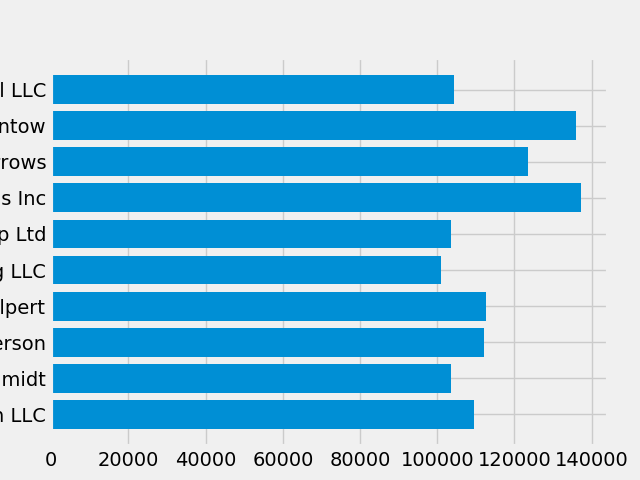

There are many styles available in Matplotlib in order to let you tailor

your visualization to your needs. To see a list of styles, we can use

pyplot.style.

print(plt.style.available)

Out:

['bmh', 'classic', 'dark_background', 'fast', 'fivethirtyeight', 'ggplot', 'grayscale', 'seaborn-bright', 'seaborn-colorblind', 'seaborn-dark-palette', 'seaborn-dark', 'seaborn-darkgrid', 'seaborn-deep', 'seaborn-muted', 'seaborn-notebook', 'seaborn-paper', 'seaborn-pastel', 'seaborn-poster', 'seaborn-talk', 'seaborn-ticks', 'seaborn-white', 'seaborn-whitegrid', 'seaborn', 'Solarize_Light2', 'tableau-colorblind10', '_classic_test']

You can activate a style with the following:

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

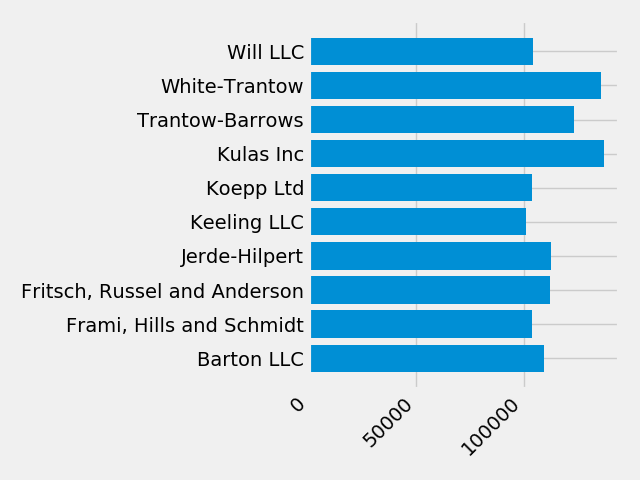

Now let’s remake the above plot to see how it looks:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

The style controls many things, such as color, linewidths, backgrounds, etc.

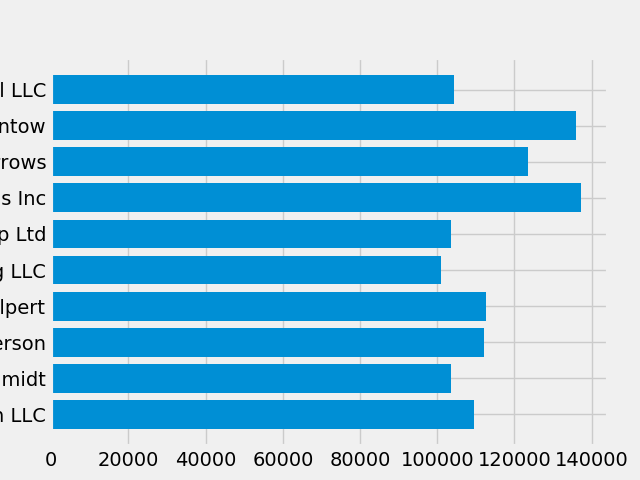

Now we’ve got a plot with the general look that we want, so let’s fine-tune

it so that it’s ready for print. First let’s rotate the labels on the x-axis

so that they show up more clearly. We can gain access to these labels

with the axes.Axes.get_xticklabels() method:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

If we’d like to set the property of many items at once, it’s useful to use

the pyplot.setp() function. This will take a list (or many lists) of

Matplotlib objects, and attempt to set some style element of each one.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right')

It looks like this cut off some of the labels on the bottom. We can

tell Matplotlib to automatically make room for elements in the figures

that we create. To do this we’ll set the autolayout value of our

rcParams. For more information on controlling the style, layout, and

other features of plots with rcParams, see

Customizing matplotlib.

plt.rcParams.update({'figure.autolayout': True})

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right')

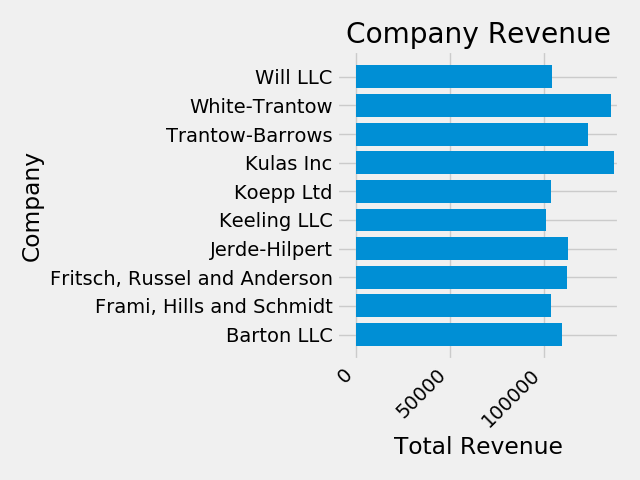

Next, we’ll add labels to the plot. To do this with the OO interface,

we can use the axes.Axes.set() method to set properties of this

Axes object.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right')

ax.set(xlim=[-10000, 140000], xlabel='Total Revenue', ylabel='Company',

title='Company Revenue')

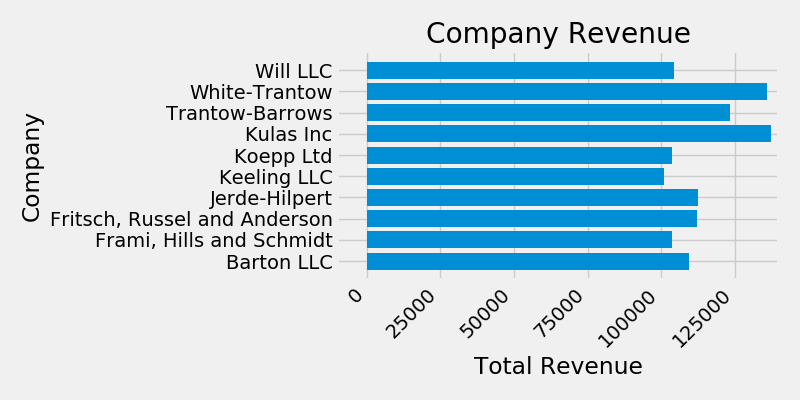

We can also adjust the size of this plot using the pyplot.subplots()

function. We can do this with the figsize kwarg.

Note

While indexing in NumPy follows the form (row, column), the figsize kwarg follows the form (width, height). This follows conventions in visualization, which unfortunately are different from those of linear algebra.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 4))

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right')

ax.set(xlim=[-10000, 140000], xlabel='Total Revenue', ylabel='Company',

title='Company Revenue')

For labels, we can specify custom formatting guidelines in the form of

functions by using the ticker.FuncFormatter class. Below we’ll

define a function that takes an integer as input, and returns a string

as an output.

def currency(x, pos):

"""The two args are the value and tick position"""

if x >= 1e6:

s = '${:1.1f}M'.format(x*1e-6)

else:

s = '${:1.0f}K'.format(x*1e-3)

return s

formatter = FuncFormatter(currency)

We can then apply this formatter to the labels on our plot. To do this,

we’ll use the xaxis attribute of our axis. This lets you perform

actions on a specific axis on our plot.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 8))

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right')

ax.set(xlim=[-10000, 140000], xlabel='Total Revenue', ylabel='Company',

title='Company Revenue')

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

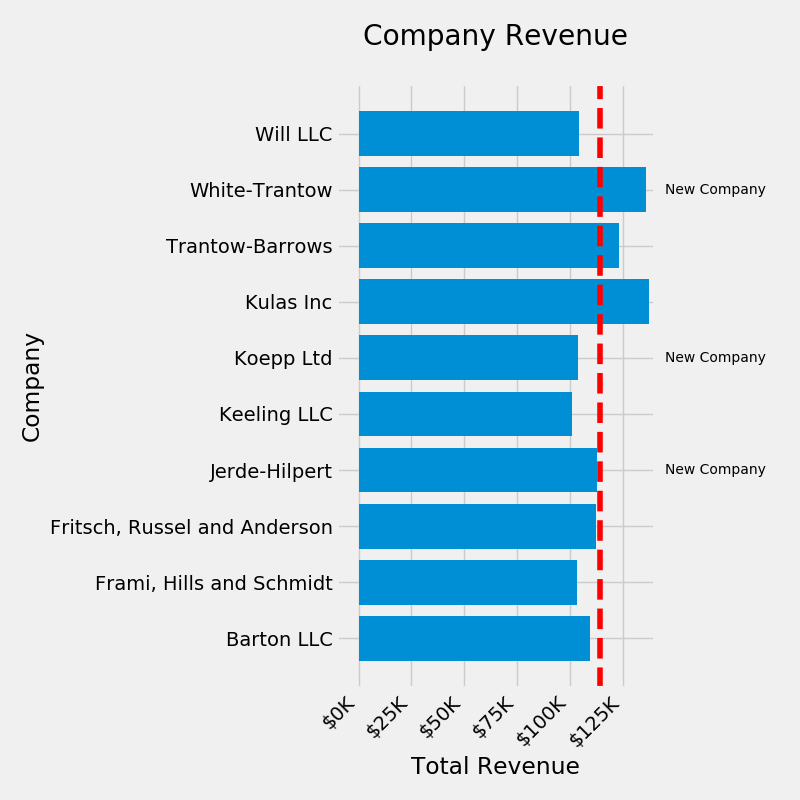

It is possible to draw multiple plot elements on the same instance of

axes.Axes. To do this we simply need to call another one of

the plot methods on that axes object.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

ax.barh(group_names, group_data)

labels = ax.get_xticklabels()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right')

# Add a vertical line, here we set the style in the function call

ax.axvline(group_mean, ls='--', color='r')

# Annotate new companies

for group in [3, 5, 8]:

ax.text(145000, group, "New Company", fontsize=10,

verticalalignment="center")

# Now we'll move our title up since it's getting a little cramped

ax.title.set(y=1.05)

ax.set(xlim=[-10000, 140000], xlabel='Total Revenue', ylabel='Company',

title='Company Revenue')

ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(formatter)

ax.set_xticks([0, 25e3, 50e3, 75e3, 100e3, 125e3])

fig.subplots_adjust(right=.1)

plt.show()

Now that we’re happy with the outcome of our plot, we want to save it to disk. There are many file formats we can save to in Matplotlib. To see a list of available options, use:

print(fig.canvas.get_supported_filetypes())

Out:

{'ps': 'Postscript', 'eps': 'Encapsulated Postscript', 'pdf': 'Portable Document Format', 'pgf': 'PGF code for LaTeX', 'png': 'Portable Network Graphics', 'raw': 'Raw RGBA bitmap', 'rgba': 'Raw RGBA bitmap', 'svg': 'Scalable Vector Graphics', 'svgz': 'Scalable Vector Graphics', 'jpg': 'Joint Photographic Experts Group', 'jpeg': 'Joint Photographic Experts Group', 'tif': 'Tagged Image File Format', 'tiff': 'Tagged Image File Format'}

We can then use the figure.Figure.savefig() in order to save the figure

to disk. Note that there are several useful flags we’ll show below:

transparent=True makes the background of the saved figure transparent

if the format supports it.dpi=80 controls the resolution (dots per square inch) of the output.bbox_inches="tight" fits the bounds of the figure to our plot.# Uncomment this line to save the figure.

# fig.savefig('sales.png', transparent=False, dpi=80, bbox_inches="tight")